Introduction to Cryptocurrencies

It seems like 2017 was the year that everyone, including our grandparents, became aware of cryptocurrencies. With news stories about the soaring or plummeting price of Bitcoin circulating on a regular basis, sentiments about the overall concept have been mixed. Some believe that cryptocurrencies will become the dominant store of the world’s economic value while others view it as modern Tulip Mania that is bound to fail.

Logos of some of the many cryptocurrencies available in 2018

Logos of some of the many cryptocurrencies available in 2018

In order to assess the potential of cryptocurrencies in general, it’s important that we explore the technical primitives on which they are built. Cryptocurrency tech isn’t exactly simple, but it relies on a few basic principles that are not hard to grasp at face value.

The Byzantine Generals Problem

The Byzantine Generals Problem goes like this: there are multiple generals each commanding part of the Byzantine army and they encircle a city that they intend to attack. If they are able to coordinate their attacks, they will overtake the city. If some attack while others retreat, they will fail.

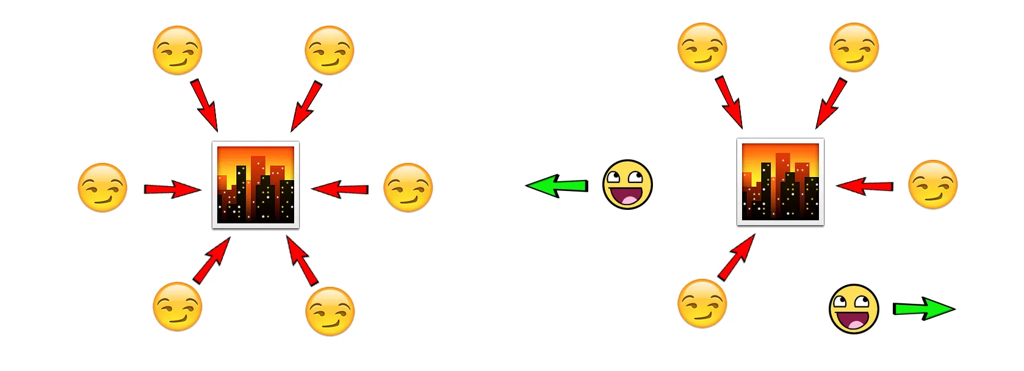

In the Byzantine Generals Problem, if all generals attack at the same time (left), they will succeed in sacking the city. However, if some of the generals decide to retreat while others attack (right), they will fail.

In the Byzantine Generals Problem, if all generals attack at the same time (left), they will succeed in sacking the city. However, if some of the generals decide to retreat while others attack (right), they will fail.

One strategy is to employ a voting system whereby each general declares his intention and is informed of all other generals’ intentions. The generals write down their votes on slips of paper and send copies to each of the other generals by foot soldier.

There are two problems with coordinating this attack:

- Messages are susceptible to tampering in transit.

- Any general may act traitorously and try to sabotage the coordinated attack by sending different messages to different generals.

This model illustrates how nodes on the Internet communicate with each other and is useful when discussing the issues inherent in achieving distributed consensus amongst disparate actors. Cryptocurrencies solve these problems through the use of public key cryptography, tamper-proof distributed ledgers (aka “blockchains”), and consensus algorithms.

Public Key Cryptography

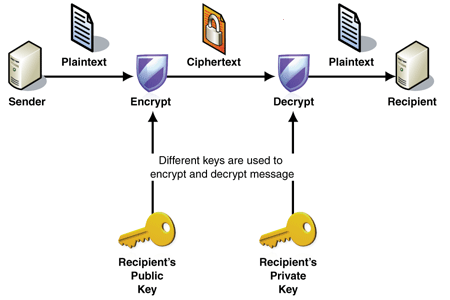

Public key cryptography is a system that provides secure communication on otherwise insecure networks, reliably verifying that a message was sent by a particular individual and that its contents were not tampered with. In this scheme, each user or node generates a private key and a public key. Each key is simply a string of characters, like vvhm5kXYvjV0dKi.

The public key is shared with the outside world and serves as a personal identifier. The private key is kept secret and is used to digitally sign (encrypt) messages coming from the user and to verify (decrypt) messages that are sent in response.

Diagram of public key cryptography

Diagram of public key cryptography

For web engineers, perhaps the most obvious use of PKC is when we run secure shell sessions. For example, if we want to connect to a remote server securely, we first need to generate a private/public key pair. In Linux this is often done using the ssh-keygen command. Running this will produce a public key stored in ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub and a private key stored in ~/.ssh/id_rsa. When we connect to a remote node using the ssh protocol, these keys, along with the keys of the remote host, are used to encrypt/decrypt all communication so message content cannot be spied on or tampered with in transit.

In cryptocurrencies, the public key serves as a “wallet address.” Similar to a telephone number or an email address, it uniquely identifies an account for a given cryptocurrency and can be freely shared with other actors. As long as a user knows the private key of an account, they control it. Users can control one or many accounts. If the private key is lost, so too is the account and all its value — forever.

The Distributed Ledger (aka Blockchain)

A ledger is simply a chronological list of transactions. Most commonly, financial ledgers are controlled by centralized, trusted authorities such as banks. We can assume that our account value is safe only as far as we trust the controlling authority. If we have reason not to trust that authority, our confidence erodes and the system becomes unstable. If we can create a tamper-proof ledger that is shared by all parties, then we no longer have the need for a central authority.

One solution, as proposed by Satoshi Nakamoto in his famous 2008 whitepaper on Bitcoin, is to use hash functions to create a linked list known as the blockchain.

Hash Functions

A hash function maps data of arbitrary size to a fixed size. For any input, it produces a fixed-length string that, for our purposes, uniquely identifies the original string. Hash functions are not reversible so it’s impossible to ascertain the input directly from the hashed value but, given an input, it will always produce the same output.

For example, we could take the novel The Fellowship of the Ring as input and produce a (semi-)unique 256-bit representation of it by passing it into a hash function. Change a single letter in the novel and a completely different looking hash value will be generated. While there are many other possible input strings that would produce the same output, there is no way for us to discover those other than to try every possible combination until we find a match. This would require more computing power than is available during all the ages of Middle Earth.

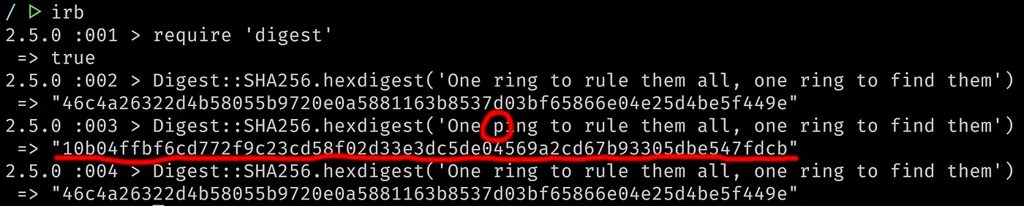

We can use Ruby’s

We can use Ruby’s digest library to demonstrate the two primary properties of hash functions: (1) The same input always produces the same output and (2) Changing a single element of the input produces a completely different output.

Hash Data Structures

The distributed ledger, or blockchain, is simply a chronological list of transactions as agreed upon by the network. Transactions (who paid whom and how much they paid) are stored in a data structure called a block. Each node in the network has a copy of the ledger and as time goes on the ledger grows a block at a time, with each node accepting or rejecting additions based on the consensus rules of the network to determine the the One True Blockchain.

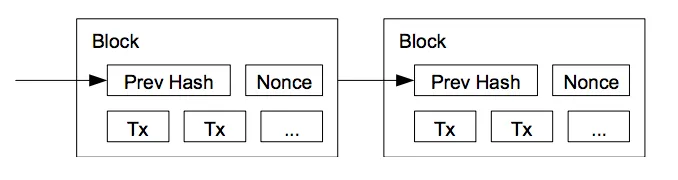

To make the ledger tamper-proof, we employ a linked list of hashes. First, we take the data representing a set of transactions (a block) and we produce a hash of it. To add another block to it, we combine the hash with a new block that represents the next set of transactions (Tx). We then hash this entire structure and include it in the next block, thus providing a fingerprint of the entire history. This method is then repeated to create a constantly growing chain that is verifiable by all nodes.

The blockchain as illustrated in the Bitcoin whitepaper

The blockchain as illustrated in the Bitcoin whitepaper

In order to tamper with the ledger, an attacker would have to search through an incredibly wide set of inputs to find the same outputs for every block in the chain between the head of the chain and the block he wants to tamper with. This is not technically feasible and so the ledger is considered tamper-proof.

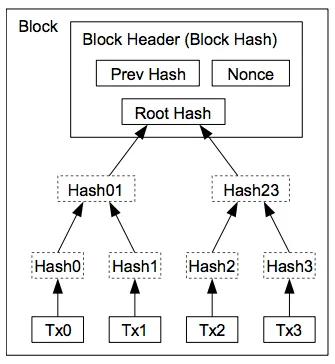

To make the blockchain easier to search and manipulate, we can organize the blocks into a binary tree structure, in much the same way that we index database columns. Each node contains a hash of all nodes below it to retain our tamper-proof scheme. This is known as a Merkle Tree. This structure provides several advantages, including the ability to easily trim older transactions to keep the overall blockchain smaller.

Binary tree of blocks (Merkle Tree) as illustrated in the Bitcoin whitepaper

Binary tree of blocks (Merkle Tree) as illustrated in the Bitcoin whitepaper

Consensus Algorithms

Okay, we’ve discussed a way to pass messages securely between nodes and we’ve got a distributed ledger that can’t be tampered with as it grows. But how do nodes agree on the content of the block that gets added to the end of the chain? Legolas may claim that Gimli sent him 100 MiddleEarthCoins while Gimli firmly denies any transaction took place. In order for the network to reach consensus, we must devise a system whereby nodes “vote” on what to add to the blockchain.

Different cryptocurrencies use different models to achieve consensus and this is where much of the complexity and nuance comes into play. Generally speaking, the two most common systems are Proof of Work (PoW) and Proof of Stake (PoS).

In PoW systems, such as the one Bitcoin employs, each node does some computational work to search through a set of inputs that will produce a specific hash. Like the dwarves toiling deep in the Mines of Moria, each node in the network has a low chance of generating (“mining”) brand new coins as they do the work of verifying the blockchain’s integrity. This is often considered “one CPU one vote” and has led to concentrated mining operations that have been criticized for their environmental impact due to high energy usage.

In PoS, each node is assigned a voting weight based on specific properties, such as how much underlying value of the currency they control or how long they have operated on the network. In these systems, mining plays no role in the verification of the blockchain and so other incentives must be used to encourage individuals to run nodes, such as implementing transaction fees for verifying the blockchain.

Entire papers are written on the nuances of these systems. For our purposes, we need not study their specifics to grasp the fact that each cryptocurrency does provide an algorithm by which consensus can be reached regarding which block will be added to the chain. We must become comfortable with the presence of malicious nodes that make false claims of the blockchain and trust in the consensus algorithm to maintain stability.

Here Legolas is claiming that Gimli sent him 100 MiddleEarthCoins (XME) for an enchanted bow while Gimli claims he’d not be caught dead carrying an Elven bow of any sort. The Cryptocouncil of Elrond has been summoned to settle the matter, thus forging another block into the One True Blockchain.

Here Legolas is claiming that Gimli sent him 100 MiddleEarthCoins (XME) for an enchanted bow while Gimli claims he’d not be caught dead carrying an Elven bow of any sort. The Cryptocouncil of Elrond has been summoned to settle the matter, thus forging another block into the One True Blockchain.

Another point to consider is that occasionally there will be “hard forks” in a given cryptocurrency, whereby a significant portion of the network adopts a fresh take on the protocol. A high profile example occurred in 2017 when Bitcoin Cash (BCH) split from Bitcoin Core (BTC). When such events occur, each node owner must side with the old protocol or embrace the new, thus creating two separate networks and two separate blockchains that fork at a specific block number. This has been observed to mirror evolution of species in the natural world, such as the Sundering of the Elves in the early days of Middle Earth.

Variations on a Theme

At the time of writing, there are ~1,400 different cryptocurrencies listed on Coin Market Cap. Why are there so many? If Bitcoin so effectively provides Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT), why the need for others?

Well, it turns out that there is no One True Solution to this problem. Variations on the basic principles provide tradeoffs in scalability, security, decentralization, privacy, transaction cost, incentives for running nodes, and initial coin distribution. Over the coming years we will find out which approaches are the most useful for various applications.

The Future of Blockchain

Since the Bitcoin network came online in 2009, other use cases for the blockchain have been invented. One of the most notable is Ethereum, a distributed computing platform developed by Vitalik Buterin that extends the mechanisms described by Satoshi Nakamoto.

Vitalik Buterin, creator of Ethereum

Vitalik Buterin, creator of Ethereum

Ethereum uses the blockchain to create a generalized shared database and provides a Turing-complete “smart contract” runtime that allows developers to create decentralized apps, or “dapps,” such as CryptoKitties. Many of the “altcoins” we see today actually run on the Ethereum network, adhering to the ERC-20 token standard. Thus, they don’t have to reinvent the blockchain wheel and instead rely on Ethereum to provide the underlying decentralized mechanisms. This leaves coin and dapp developers free to focus on their specific applications while Vitalik and friends work on improving system architecture.

As time goes on, other smart people will find new uses for blockchain technology and distributed consensus systems, potentially leading to significant societal improvements.

More to Learn…

We’ve covered only the basics of cryptocurrency technology here. I encourage you to read more on the subject and even to contribute to the growing open source projects in this space. The more tools we make, the faster we’re going to find out how valuable these technologies really are.